History of Mthwakazi

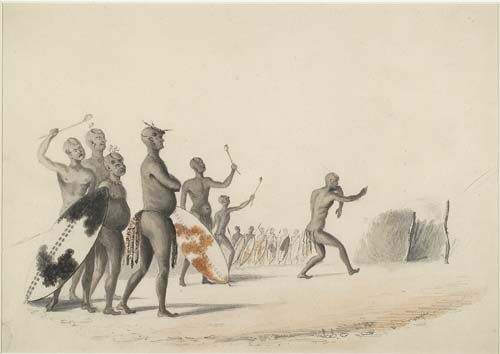

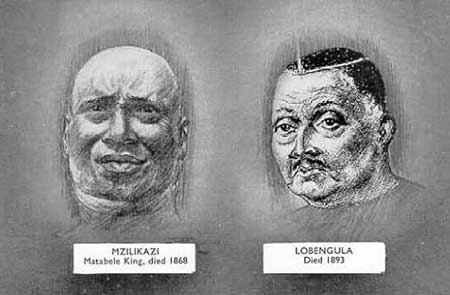

King Mzilikazi, as portrayed by Captain William Cornwallis Harris, circa 1836

Mzilikazi Khumalo -1st King of Matabeleland

Reign ca. 1823 - 1868 Coronation ca. 1820 Born ca. 1790 Birthplace Mkuze Died 9 September 1868 Place of death Matabeleland, buried in a cave at Entumbane, Matobo Hills ( 4 November 1868) Predecessor Founder (father murdered; formerly a lieutenant Zulu King Shaka) Successor Lobengula Consort several wives Offspring Lobengula (son), Nkulumane (son), and many others Royal House Khumalo; founder of the Ndebele people Father Matshobana KaMangete (c. late 1700s — c. 1820s), Mother Nompethu KaZwide, daughter of Chief Zwide of the Ndwandwe people (tribe).

Before we tell you about King Mzilikazi It

is important to understand a little bit of His background and our connection

to the ZULU Kingdom of Shaka Zulu. So let's begin with a little bit of

background information about King Shaka .

Historians have called him "Black Caesar" and compared his military skills

with Alexander the Great, and there is no doubt that the history of southern

Africa would have been very different had Shaka not lived.

Shaka Zulu: a statue in

South Africa and a contemporary sketch of the king

The man who founded the Zulu nation was born around 1787 and was murdered by

his half-brother, Dingaan, in 1828 near the banks of the Thukela (Tugela)

River. In his 41 years, he united the northern Nguni people - known today as

the Zulus - and set the tribal boundaries of the Xhosa, Sotho and Swazi

nations.

Many stories have been told of the Zulus and the tribes that grew from them

including the Shangaan and Matabele, and because we had no written language

most accounts were logged by explorers, hunters and missionaries.

But we also have a spoken version of history, handed down by grandparents,

uncles, aunts and elders to wide-eyed children sitting by the fire at night.

There under the open sky, tales are told without interruption, except from

the animals and birds that call to each other in the dark.

There, in the forests and clearings, our history has been passed from one

generation to the next. Now, with the glow of your computer screen on this

website in place of the fire, let us share it once more with each other and

with new friends from Africa and around the world.

Shaka changed the nature of warfare by inventing a short stabbing spear to

replace the long throwing assegais. This meant that his soldiers could

attack and not lose their weapons. And he established battalions and

companies similar to those used in modern armies, even though at the time

there had been no contact with western explorers. It is safe to say a lot of

the military warfare used by the West today - WAS COPIED and LEARNT from

These great AFRICAN KINGS - although they will never tell you that - BUT WE

WILL !!

One of these military units was headed by Shaka's friend and most gifted

general, Mzilikazi Khumalo, son of Matshobana.

-Mzilikazi.jpg)

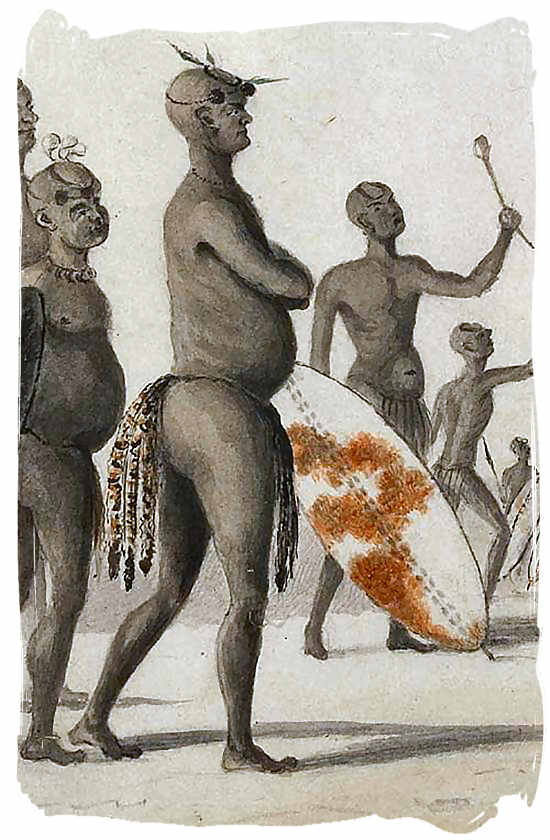

Mzilikazi, king of the

Matabele, with his royal attendants.

NOW - Mzilikazi was only three years younger than Shaka, and had become

widely respected within the kingdom for his daring raids on rival tribes.

In 1823, Shaka sent Mzilikazi on a punitive expedition against another

chief. The general was successful, but on his way back, he sent a message

asking whether he could keep some of the cattle, slaves and women captured

in the raid, and retire to an area west of Zululand to see out his days.

The law was clear: all spoils of war belonged to the king and the very

impudence of asking was enough for Mzilikazi and his family to be executed.

Sensing danger, the Khumalo army turned north and settled first at a spot

near the modern town of Bethal, 150 kilometres south of Johannesburg, which

they named Phumuleni or "The Resting Place."

Some say Shaka sent an army in persuit, others say he let the Khumalos go,

perhaps an indication of his love for Mzilikazi. Either way, rains were

good, the soil was rich, and the exiles prospered.

As their herds grew, the new king worried that Shaka would hear of their

good fortune and grow jealous, so he moved his people to where Pretoria now

stands, then to Brits, and finally to a site on the Groot Marico River near

Botswana.

Over the next decade, Mzilikazi and his warriors came to dominate the entire

northern region of South Africa, destroying local kingdoms and pushing

others like the Shangaan, Venda, Pedi and Tswana off the best land.

Their rivals named them amaNdebele, "the people of tall shields" and a

nation was born.

The Roman empire became great because, on conquering another country, they

would incorporate those who surrendered to create an ever-greater force. And

this is how the Matabele built their numbers.

Men and women of working age who would not submit to the new order were

taken as slaves. Shaka was, without doubt, the biggest slave-owner in the

history of southern Africa and Mzilikazi became a close rival. This may be

difficult to understand in our modern world, but it was in line the great

empires of West and East Africa, the Incas of South America and even China.

In lands damaged by war, and cattle driven off by the victors, anyone left

behind would starve. Instead, they were either brought into the winning

tribe, or kept as slaves who would, in time, be assimilated. And children of

these workers were full citizens at birth.

Zulu is a rich language, but as more villages and settlements fell to the

Matabele, their languages enriched our own so that, now, isiNdebele has a

greater number of words than Zulu, along with variations of pitch and tone.

In South Africa, a Zulu will spot a Matabele as soon as hears the person

talk.

By 1830, the area ruled by the House of Khumalo covered modern-day Gauteng

and much of the Free State, Mpumalanga, Limpopo Province and even part of

North West.

Zulu traditions were maintained. Young men were all in regiments and were

forbidden to marry without permission of the king.

The Matabele and Zulu traditions

continue to this day in ceremonies for special events.

From the age of seven or eight, boys were tasked to herd livestock, and

spent their leisure time fighting with sticks and talking of the day when

they would be old enough to join the army.

By 12, a boy could drive cattle for 10 hours, walking barefoot over stones

and thorns without cutting his feet.

The Matabele could count, but they had no starting point of time like our BC

and AD positioned around the birth of Christ. Instead, the years were

numbered in relation to various events. For example, someone was said to

have been born two seasons before the flood or eight years after the great

fire or at the time when lightening killed 14 cattle on a hilltop. As a

result, few could be sure just how old they were.

Boys tended to work and play in groups based on age, but when it came time

to join a regiment, each teenager would stand naked in front of the unit

commander. If the recruit looked as if he was close to manhood, he was

allowed to proceed. If he appeared to still be in the early stages of

puberty, he had to wait another year.

Women had roles depending on their age, and there was a strict code of

respect and discipline. Planting, cooking, harvest, collecting wild fruits

and maintaining the home were all important duties along with the most

treasured role of raising children.

Like Solomon in the Bible, Mzilikazi was expected to sit in judgement over

squabbles between his subjects. First, an issue would go before the induna

or chief. If nothing was resolved, the king held court and his word was

final.

By this time, the first white missionaries and explorers had entered the

region and, provided they asked permission to pass, all were welcome to call

on the king.

Among his regular visitors were Robert Moffat who had set up a mission at

Kuruman in the northern Cape, and his son-in-law, David Livingstone. French

and American missionaries asked permission to settle in the area and, under

the king's protection, were not only kept safe, but came to be looked on as

friends. Dr Moffat, especially, became so close that the king referred to

him as, "my special guest". Moffat was fluent in Zulu and the two men would

sit up all night talking politics, while the missionary tried in vain to

convert his host to the Church.

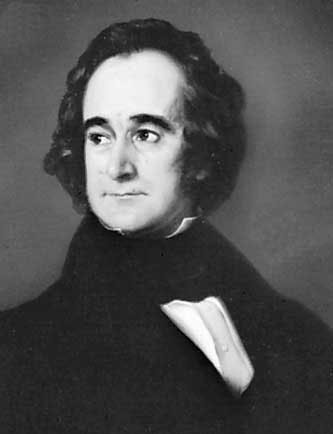

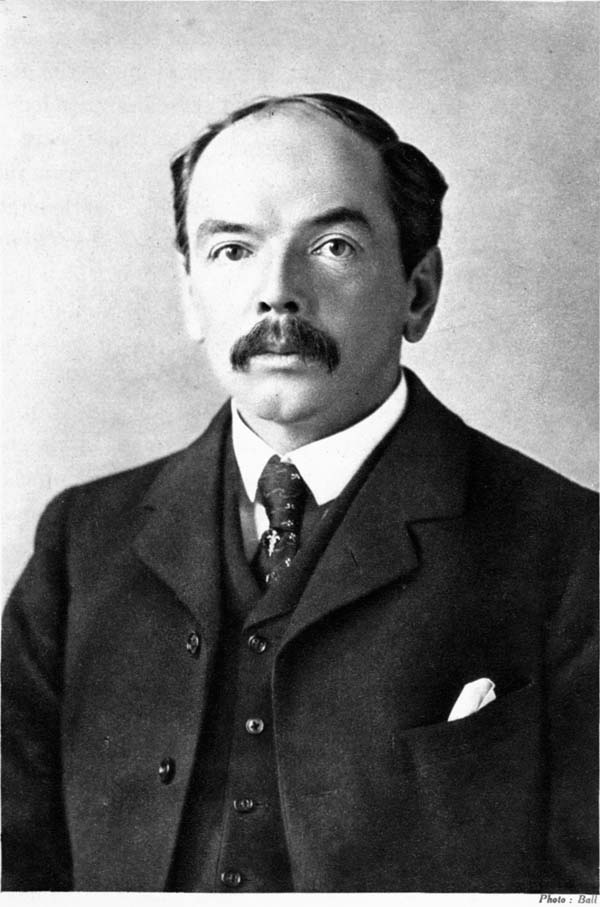

Robert Moffat (left) spoke fluent

Zulu and was a close friend of the king, as was his son-in-law, David

Livingstone (right).

Throughout the year, there were feast days and celebrations: the first

rains, first fruits on the trees, birth of the impala antelope in the wild

around December, flooding of the rivers, harvest of crops, the coming of

snow.

At every event, women would sing, warriors would dance and the nation came

together in unity, reaffirming itself before the ancestral spirits and to

every member of the tribe as a people united by language, culture, tradition

and loyalty to the king and to each other.

The Matabele were here to stay.

But Africa was changing. The great Shaka had been assassinated and King

Dingaan heard exaggerated reports about the wealth of Mzilikazi whose cattle

were so numerous, they stretched over plains, into the mountains and on

through neighbouring valleys, almost without end.

A series of droughts had cut the Zulu

herd, and Dingaan sent his armies north to raid the Matabele.

Almost a thousand kilometres away in the Eastern Cape, the new British

rulers were sailing their ships from England, laden with farmers, tradesmen

and their families who, it was hoped, would develop the area around Port

Elizabeth and East London.

The Dutch, who had been in the Cape since 1652, were not happy with the

British influx and in 1834 large numbers packed their wagons and headed

north in what became known as the Great Trek.

In covered wagons, the Voortrekkers

(Dutch = first travelers) pushed north to escape British rule.

In 1835, these pioneers, forefathers of today's Afrikaners, crossed the Vaal

River and established themselves less than 100 kilometres from the Matabele.

Unlike earlier travellers, they refused to seek permission from the king,

and war was inevitable.

In August 1836, a Matabele patrol killed an Afrikaans hunting party. The

whites retaliated and Mzilikazi sent his army in response.

War came on 16 October at the Battle of Vegkop in northern Free State. The

Voortrekkers placed 50 wagons in a circle and held off more than 4 000

warriors with their guns, only to see the Matabele withdraw with most of

their cattle and nearly 50 000 sheep.

Not long after, Dingaan's army made a surprise raid on the Matabele and

while Mzilikazi's forces were regrouping, the Trekkers attacked.

The tribe responded by burning their settlements and pushing north across

the Limpopo.

A great number of books have been written about the battles between the

Afrikaners, Zulus and Matabele, and the Voortrekker Monument near Pretoria

has an excellent display and a well-balanced account of the war, laid out in

models, maps and wallcharts.

Of the many stories that came from this history, there is one that runs rich

in Matabele legend, even though we are never likely to know the truth.

During the battles of August 1836, the warriors raided the wagons of Barend

Liebenberg.

Liebenberg was a difficult man who argued constantly with the other Trekkers

and, as a result, he had pitched camp with his family and servants some

distance away. The Matabele overran the position and slaughtered the entire

party, except for three children -- two girls and a boy -- who were taken

back as a gift for Mzilikazi.

The king was angry, saying he did not regard children as prisoners of war

and wanted them returned to the Trekkers. But with the conflict reaching its

height this was not possible and, when the tribe went north, they took the

children with them.

For years, travellers to Matabeleland spoke of seeing a number of whites who

seemed to be part of the tribe. A young man -- possibly the Liebenberg boy

-- had a senior position in one of the regiments and a teenage girl had

taken on the role of nursemaid to Mzilikazi's youngest son, Lobengula.

In our own folk takes, it's said that the trust Lobengula would eventually

place in the British may have come from being raised by a white woman.

As they moved north, the Matabele army split, a tactic often used when they

feared that an enemy may be following.

In this case, however, the two patrols became separated, with one under

command of the king and the other led by his son, Nkulumana who had been

named after Robert Moffat's mission at Kuruman. There is no letter "R" in

the isiNdebele language, and this was how the word sounded to their ears.

Mzilikazi pushed into the land of the Tswana people, then turned east about

80 kilometres from the Zambezi River. Nkulumana marched across the Limpopo

and settled near the Matobo Hills.

A year passed and there was no word from Mzilikazi. In September 1839, as

winter gave way to spring, custom demanded that the new settlement should

celebrate ncwala or the ceremony of first fruits, but a king had to be

present before the event could take place.

Believing that Mzilikazi had died in the desert, the tribe placed Nkulumana

on the throne.

Not far from Hwange National Park, news reached Mzilikazi that he had been

replaced. He called his followers together and they marched south, reuniting

with his sons early in 1840.

Nkulumana sent a party to meet his father, and the king, learning that they

really had thought him dead, forgave the treason. Until, that is, he asked

what great sorrow and mourning had filled the land on news of his death.

But, exhausted from their journey, the settlers had not held the usual

ceremonies on the loss of a king. Mzilikazi was angrier than ever and he had

Nkulumana and all the other sons and their advisors taken to a nearby hill

and executed.

Today that mountain is known as Ntabazinduna or the hill of chiefs.

Only the youngest son, Lobengula, was spared when his white nursemaid hid

him in the Matobo mountains.

The death of so many from the royal house gave rise to a fresh name for the

site they had chosen as the Matabele's new home, and it was christened, "the

place of great killing," which in our language translates as Bulawayo.

The next 50 years became a time we look back on as the greatest period in

Matabele history.

King Mzilikazi ruled wisely and grew in his people's affection. Unlike Shaka

who had seen several attempts on his life before being murdered by his

brother, Mzilikazi lived in peace and, from around the world, traders,

hunters and explorers came to Bulawayo.

The Voortrekkers settled in our old lands, creating two countries which they

called the South African Republic (ZAR or Transvaal) and the Orange Free

State.

Having met the Matabele in battle, they made no effort to cross the Limpopo

and in the ZAR, President Paul Kruger established diplomatic relations with

Matabeleland.

History told well must be the truth, and we would have to accept that to the

north and west, the Matabele were not always good neighbours.

We raided the Tswana people for cattle and the great great grandfather of

current Botswana president, Ian Khama, shot at Mzilikazi who carried the

bullet in his body for the rest of his life.

The remainder of what is now Zimbabwe was mostly occupied by the Shona, a

tribe that originated in eastern Congo and moved down Africa over a period

of more than 800 years until around 1200 AD they crossed the Zambezi River

and colonised much of modern Zimbabwe. The Shona are related to the Venda

people in South Africa and the Ndau of central Mozambique.

For 100 000 years or more, one people occupied central and southern Africa.

The Bushmen or San grew no crops and kept no cattle, but hunted game and

gathered wild fruits. They lived in caves where they drew their life in

pictures on the wall and this art - some of the oldest in the world - can

still be seen today.

For 100 000 years, only the Bushmen or

San occupied hinterland of southern Africa where their art can still be seen

in caves where they lived.

The Shona brought with them cattle and a great skill in growing crops. The

San saw cows as just another animal to be hunted, and conflict broke out

between the two until the Shona exterminated the Bushmen completely, driving

the last of their number into Botswana.

Around 1500AD, the Shona built the Rozvi kingdom near Masvingo.

They traded with merchants from the Middle East and possibly even China,

selling gold, silver and slaves in exchange for beads and fabric.

The Shona Rozvi kingdom

The Matabele sent raiding parties into Mashonaland, taking cattle and

eventually imposing a tax on the Shona who had little military tradition and

were unable to resist the warrior nation.

Conquering the neighbours was a common event in history throughout Africa,

and in Europe, Asia and South America. It established the world's great

nations including Russia, China, India, Germany, France and Britain, and was

seen as a normal part of foreign policy. And it was this policy of expansion

that saw first Portugal, then Britain, Germany, Spain and Belgium taking

chunks of Africa as colonies from which they would draw minerals, timber

and, in some cases, slaves.

Mzilikazi died on 9 September, 1868 and was succeeded by his son, King

Lobengula

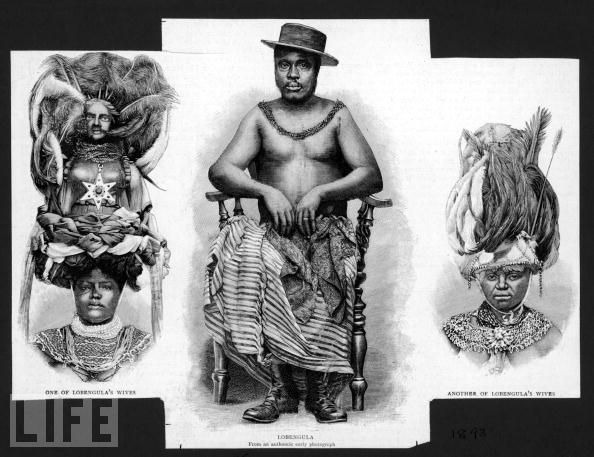

King

Lobengula of Matabeleland

1893: who led a revolt against encroaching British gold

miners, flanked by images of two of his wives.

Reign September 1868 - January 1894

Coronation 1869

Born ca. 1845

Birthplace Matabeleland

Died ca. January 1894

Place of death ca. 70 km south of the Zambesi river in Matabeleland

Predecessor Mzilikazi (Father)

Consort Lozigeyi (1st royal wife), Lomalongwe (2nd royal wife)

Offspring Mpezeni (royal son and heir) born in Bulawayo ca. 1880 and died at

Somerset Hospital on 9 December 1899 of pleurisy, Njube (royal son),

Nguboyenja (royal son) sent to Cape Town after death of Lobengula and buried

at Entumbane near to Mzilikazi, Sidojiwa born at Nsindeni ca. 1888 (royal

son) and died 13 July 1960 (buried at Entumbane near to Mzilikazi), and at

least one daughter

Royal House House of Khumalo

Father Mzilikazi Khumalo, first King of the Ndebele people

Mother

Princess of the Swazi House of Sobhuza I., an "inferior" wife of Mzilikazi

Lobengula Khumalo

After the death of Mzilikazi the first king of the Matabele nation in 1868

the izinduna, or chiefs, offered the crown to Lobengula, one of Mzilikazi's

sons from an inferior wife. Several impis (regiments) disputed Lobengula's

assent and the question was ultimately decided by the arbitration of the

assegai, with Lobengula and his impis crushing the rebels. Lobengula's

courage in this battle led to his unanimous selection as king.

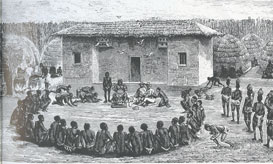

The coronation of Lobengula took place at

uMhlanhlandlela, one of the principal military towns. The Matabele nation

assembled in the form of a large semicircle, performed a war dance, and

declared their willingness to fight and die for Lobengula. A great number of

cattle were slaughtered and the choicest meats were offered to Mlimo, the

Matabele spiritual leader, and to the dead Mzilikazi. Great quantities of

millet beer were also consumed.

About 10,000 Matabele warriors in full war costume attended the crowning of

Lobengula. Their costumes consisted of a head-dress and short cape made of

black ostrich feathers, a kilt made of leopard or other skins and ornamented

with the tails of white cattle. Around their arms they wore similar tails

and around their ankles they wore rings of brass and other metals. Their

weapons consisted of one or more long spears for throwing and a short

stabbing-spear or assegai (also the principal weapon of the Zulu). For

defence, they carried large oval shields of ox-hide, either black, white,

red, or speckled according to the impi (regiment) they belonged to.

The Matabele maintained their position due to the greater size and tight

discipline in the army, to which every able-bodied man in the tribe owed

service. "The Ndebele army, consisting of 15,000 men in 40 regiments [was]

based around Lobengula's capital of Gubulawayo."

Lobengula was a big, powerful, man with a soft

voice who was well loved by his people but loathed by foreign tribes. He had

well over 20 wives, possibly many more. His father, Mzilikazi, had around

200 wives. It is said he weighed about 19 stone (120 kg or 265 lb) and he

was a fine warrior though not an equal of his father. Life under Lobengula

was less strict than it had been under Mzilikazi, although the Ndebele

retained their habit of raiding their neighbours.

By the time he was in his 40s, his diet of traditional millet beer and beef

had caused him to be obese according to European visitors. Lobengula was

aware of the greater firepower of European guns so he mistrusted visitors

and discouraged them by maintaining border patrols to monitor all

travellers' movements south of Matabeleland. Early in his reign he had few

encounters with white men (although a Christian mission station had been set

up at Inyati in 1859), but this changed when gold was discovered on the Rand

within the boundaries of the South African Republic in 1886.

Lobengula had granted Sir John Swinburne the right to search for gold and

other minerals on a tract of land in the extreme south-west of Matabeleland

between the Shashi and Ramaquabane rivers in about 1870, in what became

known as the Tati Concession. However, it was not until about 1890 that any

significant mining in the area commenced. Lobengula had been tolerant of the

white hunters who came to Matabeleland and he would even go so far as to

punish those of his tribe who would threaten the whites. But he was wary

about negotiation with outsiders and when a British team, F. R Thompson,

Charles Rudd and Rochfort Maguire, came in 1888 to try to persuade him to

grant them the right to dig for minerals in additional parts of his

territory, the negotiations took many months. Lobengula only gave his

agreement to Cecil Rhodes when his friend, Dr. Leander Starr Jameson who had

treated Lobengula for gout once before, secured money and weaponry for the

Matabele in addition to a pledge that any people who came to dig would be

considered as living in his Kingdom.

As part of this agreement, and at the insistence of the British, neither the

Boer nor the Portuguese would be permitted to settle or gain concessions in

Matabeleland. The 25-year Rudd Concession was signed by Lobengula on 3

October 1888 and by Queen Victoria on 20 October 1889.

Lobengula said ...

" The chameleon gets behind the fly, remains motionless for some time, then

he advances very slowly and gently, first putting forward one leg and then

another. At last, when well within reach, he darts his tongue and the fly

disappears. England is the chameleon and I am that fly."

—Lobengula

Cecil J Rhodes said ...

" The British happens to be the best people in the world, with the highest

ideals of decency and justice and liberty and peace, and the more of the

world we inhabit, the better it is for humanity."

—Cecil Rhodes

King Lobengula maintained good relations

with all comers, and Matabeleland was recognised as a sovereign state.

Also happening at this junction in HIstory was the beginning of the so

called "scramble for Africa". The Berlin Conference (1884-1885) was to cut

Africa into spheres of influence for the European powers, eager to establish

colonies. The Ndebele kingdom's geographic position made it the center

across which the ambitions of the Europeans collided. Lobengula's sympathies

and soft spot for the missionaries, which he had inherited from his Father,

King Mzilikazi, eventually led to the downfall of the Matebele Kingdom.

Lobengula's Kingdom encompassed both Matebeleland and Mashonaland, but this

country was rich in natural resources, which was the interest of European

settlers. Through various concessions and treaties, Lobengula was tricked

into signing over his Kingdom to the authority of Cecil John Rhodes.

Over the next 20 years, the European powers divided Africa between them and it became clear that, sooner or later, Matabeleland would become a target for colonisation. The famous hunter, Frederick Courtney Selous, became a regular visitor to Bulawayo and a friend of Lobengula. He brought tales of the outside world, of how Africa was changing, and warned the king that his territory was in danger.

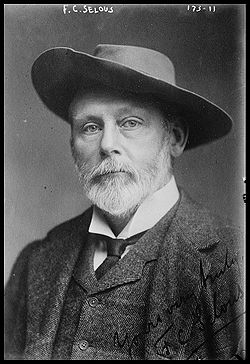

Frederick Courtenay Selous was one of

the first hunters to explore Matabelaland.

Ambassadors from Germany, Portugal, France and even Russia called on

Bulawayo, each hoping to strike a deal. All were well received, but went

home with news that a great army protected this country, and while the rest

of Africa fell, no one was willing to try their luck with Matabeleland.

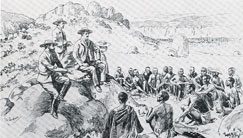

King Lobengula holds court outside his

modest sleeping hut at Bulawayo.

In 1879, the British conquered the Zulus and colonised their country. The

British had also gone to war with the Transvaal, but were defeated.

The mineral wealth of South Africa had largely been developed by Cecil John

Rhodes, who came to Africa from England in 1870, and 20 years later was the

richest man in the world.

Cecil Rhodes imagined a British corridor

across Africa from Cape Town to Cairo and used his own fortune to colonize

territories north of the Limpopo River.

Rhodes dreamed of uniting all of east and southern Africa under British

rule, but after the expensive campaign in Zululand and their defeat again

the Transvaal, the government in London was not keen on a war with the

Matabele.

Cecil Rhodes; from Cape Town to Cairo

The Portuguese who controlled Angola to the west and Mozambique in the east

were also looking at creating a strip across Africa to stop British

expansion, while the Germans longed to link up South West Africa (Namibia)

with their east African territories of Rwanda, Burundi and Tanganyika (now

Tanzania).

But it was the abandoned Shona structure at Great Zimbabwe that caused the

most trouble. In 1871, German hunter Karl Maunch had seen the stone walls

and towers and convinced himself that it had been the source of gold for

Solomon's temple as told in the Bible.

Rhodes believed that even greater gold fields than those in Johannesburg lay

to the north, and after many missions to Bulawayo, he recruited John Moffat

- son of Robert who had been a friend of both Mzilikazi and Lobengula - to

negotiate with the king.

Moffat convinced Lobengula that Rhodes would protect him from other

colonisers. But it was Charles Rudd, who had worked with Rhodes when they

were both young and poor, who eventually talked the king into signing a deal

that allowed mining and settlement in Mashonaland which was, by now, under

control of the Matabele.

The British sent a missionary, John Smith Moffat, to Lobengula's court, to

keep an eye on British interests. Moffat was the son of a missionary who had

made a name for himself among the Botswana to the south. Lobengula welcomed

him as a bearer of spiritual tidings. The missionary persuaded the King to

sign a treaty with the British, by which Lobengula undertook not to cede

land to any power without the consent of the British. Sections of the army

opposed the treaty, on the score that it surrendered the sovereignty of the

Ndebele to the British. Lobengula believed and argued that the man of God

wanted a friendship which would protect that very sovereignty.

Rhodes followed the Moffat manoeuvre with a delegation to Lobengula, which

asked for, and got, permission for Rhodes to trade, hunt, and prospect for

precious minerals in Ndebele territory. This came to be known as the Rudd

Concession (1888). In return Rhodes offered 1, 000 Martini-Henry rifles,

100, 000 rounds of ammunition, an annual stipend of £1,200, and a steamboat

on the Zambezi. He formed the British South Africa Company to explore the

concession, and organized 200 pioneers, promising each a 3, 000-acre farm on

Ndebele land, and sent them north with a force of 500 company police.

Rhodes's plans infuriated the Ndebele. Lobengula cancelled the concession

and ordered the British out of his country. As he had only spears to ensure

respect for his commands, the British ignored his order, proceeded to

complete the road link with the south, and brought in more settlers.

Cecil Rhodes used his own money to finance a pioneer column, led by Selous,

and on 11 July 1890 they crossed into Matabeleland, setting up bases at Tuli,

Fort Victoria (Masvingo) and, on 12 September 1890, at Salisbury, now known

as Harare.

The pioneers had been told that the Shona lands were rich in gold. In fact

they found very little, and as malaria and other tropical diseases crippled

the settlement at Fort Salisbury, stories spread that the real mineral

wealth lay in Matabeleland.

Despite Lobengula's best efforts at keeping peace with his new neighbours,

war broke out but the new Maxim machine guns that Rhodes had sent with his

forces were too much for even the great armies of Matabeleland, and with his

people defeated Lobengula, set fire to Bulawayo and fled north.

In the battles that marked the end of Lobengula's Reign, there were many

acts of heroism on both sides but two are worth special mention.

The Matabele were impressed by often

fatal acts of bravery from some of the white pioneers.

Near Masvingo where the main war took place, our armies had been ordered to

take the British position and, when the Maxim guns started firing, the

Matabele rushed into the flow of bullets, over and over, in a failed effort

to reach the fort. An order to attack meant risking your life, no matter how

strong the enemy, and to die in battle was the only honourable way for a

warrior.

On 3 December, 1893, a British patrol was trying to capture the king who had

by now left Bulawayo. A small party went forward led by the Scottish Major

Alan Wilson and his American scout, Frederick Burnham. Wilson and 33 men

were cut off by floods on the Shangani River about 40 kilometres north-east

of Lupane. Burnham and two others managed to cross and went for help, but

while they were gone, what remained of Lobengula's army attacked.

Major Alan Wilson who died at Shangani.

Wilson and his volunteers fought bravely and killed close to 500 Matabele.

When they ran out of ammunition, the men sang "God Save the Queen." Both of

Wilson's arms had been broken by assegais and he had finally taken cover

behind the body of his dead horse. When he realised that he was the last

survivor, he stood up and walked towards the Matabele at which point a young

warrior ran forward and speared him in the chest.

With the battle over, the Matabele gave the royal salute, Bayete! They had

been impressed by the bravery of the pioneers, and the story is still told

in our culture. The Matabele have great respect for courage, regardless of

who wins the fight. Rhodes was in South Africa, but his senior man, Leander

Starr Jameson, arrived in Bulawayo from Salisbury shortly after the king had

left.

Jameson, a medical doctor, sought to limit the loss of life and sent a

letter to Lobengula who was by this time near the Bubi River.

The note read:

"I send this message in order, if possible, to prevent the necessity of any

further killing of your people or burning of their kraals. To stop this

useless slaughter you must at once come and see me at Bulawayo, when I will

guarantee that your life will be saved and the you will be kindly treated. I

will allow sufficient time for this message to reach you and return to me

and two days more to allow you to reach me in your wagon. Should you not

then arrive I shall at once send out troops to follow you, as I am

determined as soon as possible to put the country in a condition where

whites and blacks can live in peace and friendliness."

Leander Starr Jameson tried to make

peace, but Lobengula's reply was stolen by soldiers along with an offering

of gold.

Lobengula received the envelope and sent a reply that he was willing to meet

Jameson and make peace. As a sign of good faith, he included two bags of

gold dust.

The parcel was handed to two private soldiers, Daniels and Wilson, who

destroyed the note and stole the gold.

They were later tried and sentenced to 14 years jail, but they appealed on

grounds that the magistrate newly arrived at Bulawayo only had power to pass

sentences of up to three months. The men were released, but their act of

selfishness cost many lives on both sides and destroyed what little chance

there was for peace.

The British rounded up the huge herds of Matabele cattle and, in one of the

greatest thefts in the history of southern Africa, the livestock was divided

between the pioneers and Rhodes' British South Africa Company. This was a

cause of lasting resentment.

What happened to Lobengula remains a mystery. Some say he died on the

journey and his body was hidden in a cave. Others tell of how he crossed

into Zambia, living quietly under a false name until his death in 1923.

Over the next few years, there were several attempts to revive the kingdom

but the rebellions always faltered when machine guns opened fire on warriors

armed only with spears.

Eventually, Cecil Rhodes travelled from his home in Cape Town to Bulawayo

and sent word to the fighters that he had come to end the war. They replied

that he should meet them, alone and unarmed, at a clearing in a forested

section of the Matobo Hills.

To their surprise, Rhodes agreed and at the appointed time, he walked out

onto the open grassland and sat on a rock. Impressed by his bravery, the

warriors and their chiefs came out of hiding and sat in a half-circle around

him and there they made peace.

Today, Cecil Rhodes is buried in the Matobo

Hills and the Matabele have a special guard to protect his grave. In war and

in peace, we respect courage and we honour the dead, and the grave of the

man who conquered us will forever be sacred ground in our kingdom.